This

is a story

about a tumor that

expands

and never stops.

Chapter 1

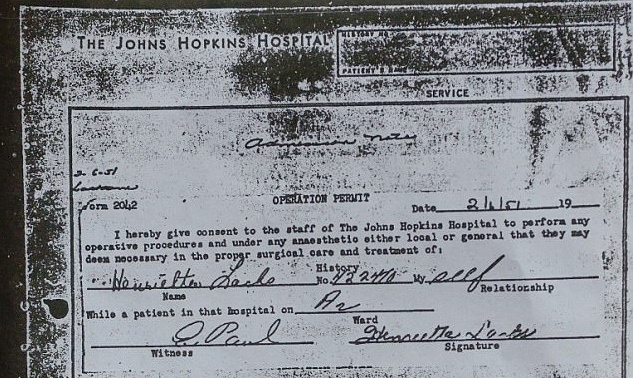

It begins in 1950. A black woman in Baltimore is in her bathroom and she discovers pretty much all on her own that she has cancer.

It’s all a bit of a mystery how she initially knew this, but she knew it was there. She had told her cousins for awhile that she thought there was something wrong her, with her womb. And she climbed into her bathtub and she slid her fingers up inside of herself and found this lump.

First she went into her local doctor. The guy she eventually ended up seeing at Johns Hopkins University was Dr. Howard Jones.

"I never saw anything like it before or after. And this didn’t look like a normal tumor. It was, it was deep purple and about as big as a quarter, sort of shiny. Very soft. That was another thing about it. When you touched it, you might think it was red and jello. There was something really strange about the way it looked."

- Dr. Howard Jones

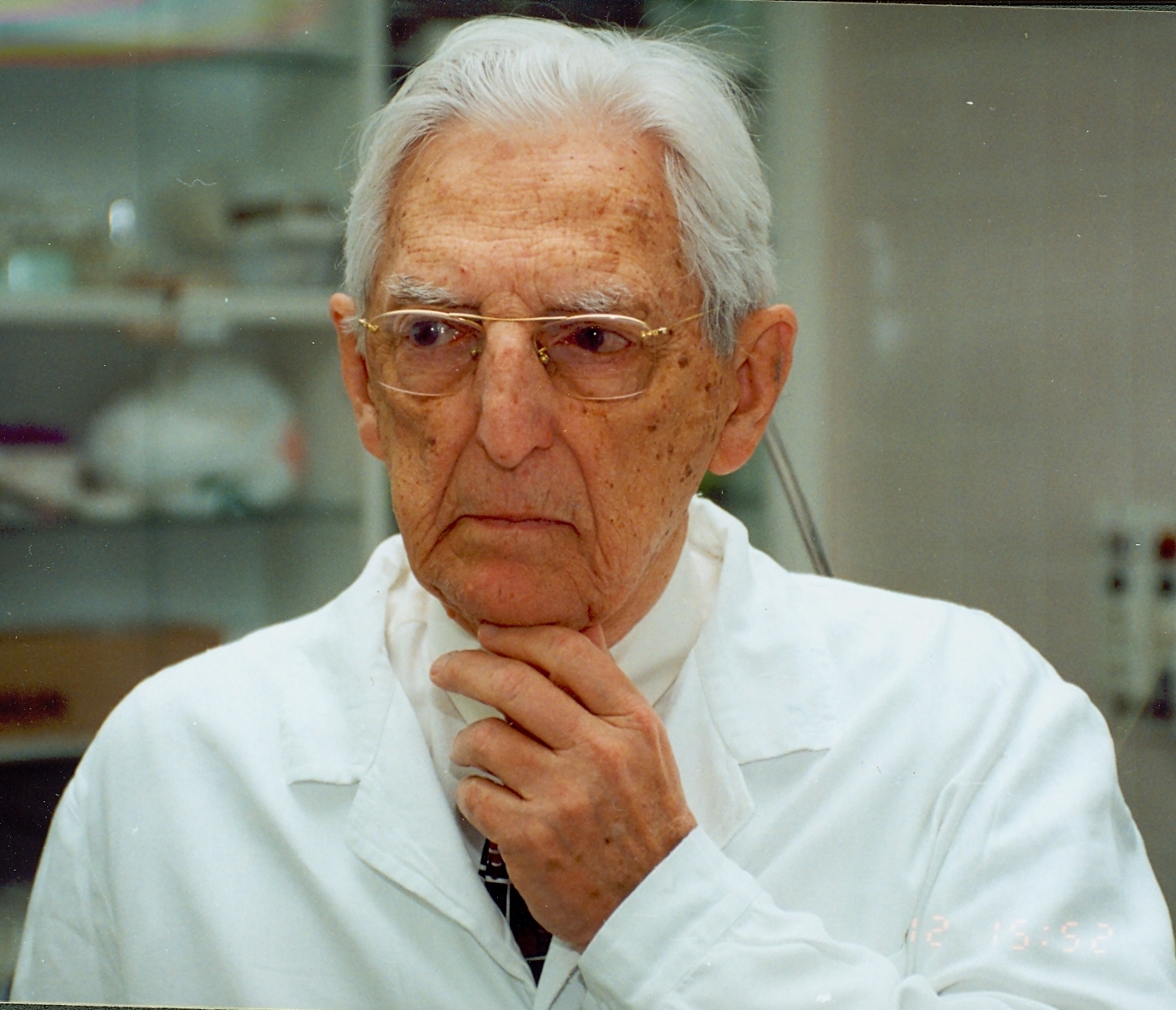

He decided to take a sample. Doctors would cut off these little teeny tiny pieces and put it in a tube. And one would go to the lab for diagnosis. And in this case, since it was Hopkins, they would take an extra piece and give it to a man named George Gey. He was a researcher who worked at Hopkins. Gey had a deal with the clinic that anytime they got a patient with cervical cancer, they’d give him a tiny piece of the tumor.

His main mission--actually not just his, scientists everywhere were trying to do this, they wanted to find a way to grow human cells outside of a human being in a dish. George Gey had been trying to do this, working on this for decades.

This is one of the basic things you need to study human biology. It’s like having a tiny bit of a person in a lab that’s detached from them so that you can do whatever you want because you can’t bombard some person with a bunch of drugs and just wait to see how much they can tolerate.

So, later that day, George Guy walked in and handed Margaret, his wife and lab assistant, a tube of a little chunk of a nameless woman’s cervical cancer inside

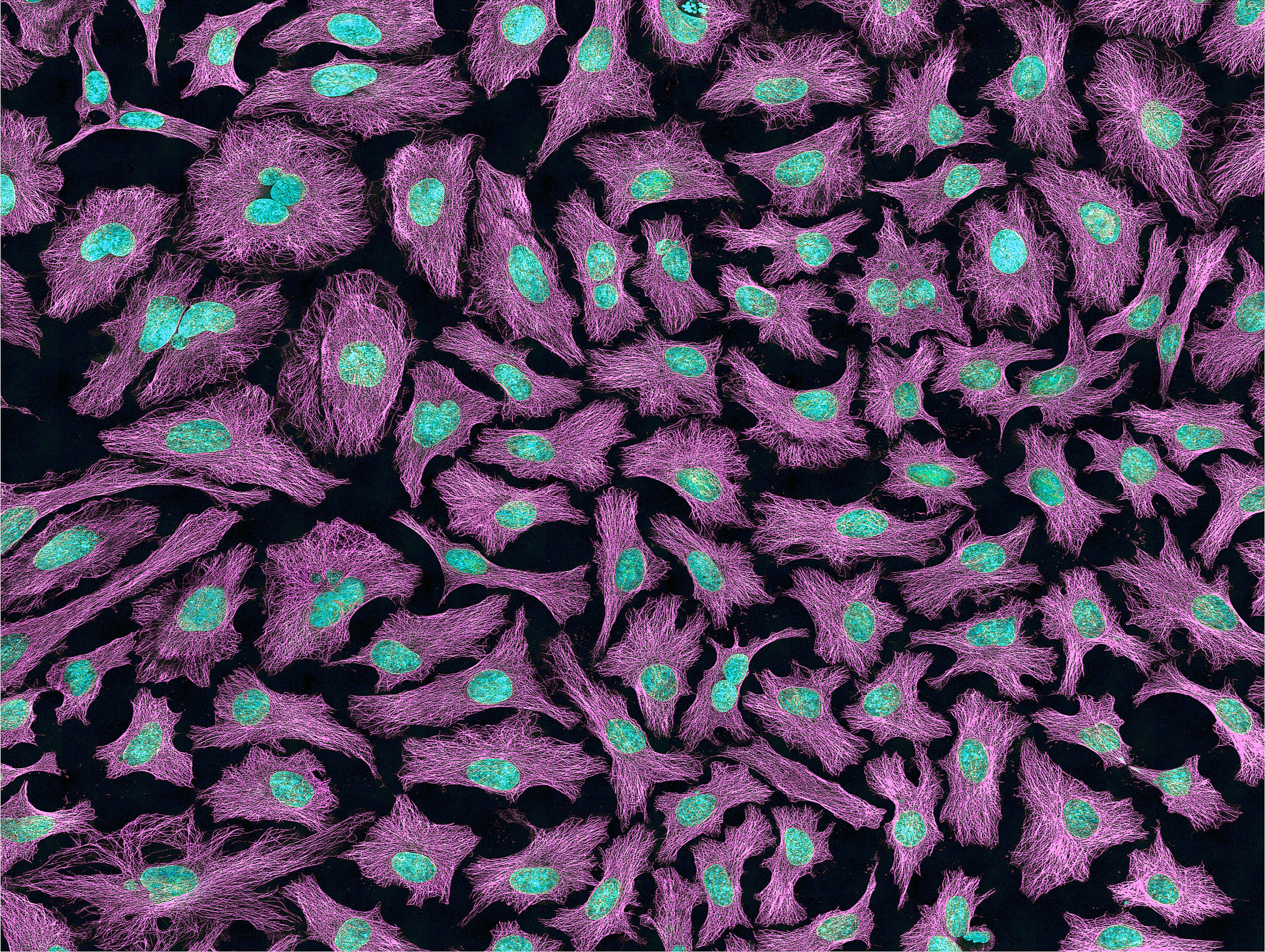

She put them in a dish, gave the some food, and turned on all the machines and left. When checked on them the next day, they hadn’t died. So she came back the next day. And they were growing. And then the next day. Still growing.

They allegedly doubled in size every 24 hours. Margaret had to keep transferring them into new containers because they never stopped growing.

While the woman who had spawned all these cells died, her cells were still going strong.

Chapter 2

It wasn’t long after that George Gey appeared on TV, holding in his hand a little bottle of cells they have grown

Why hers just sort of took off and grew and the other ones that they had tried before didn’t is just a little bit of a mystery. Nobody really knows, but Dr. Gey knew what he had. So early on, right after this woman died, George Gey sent Margaret back to get more cancer cells from the corpse.

"He sent me down to the morgue. The coroner took some samples out and gave them to me. And She’s lying out there, she’s already open. I couldn’t look at her face. I couldn’t look at her. The only thing I looked at were her toes and they had chipped nail polish on them and that was really like, 'Oh this is a real person'."

- Margaret Gey

Over the next several months, while this woman’s body lay decomposing in the ground, George Gey and Mary produced hundreds of thousands of her cells, her tumor cells. And he named them the HeLa strain, after Henrietta, but no one would know that for another 20 years.

Contrary to expectations, George Gey didn’t try to make any money off of the cells because it could be so beneficial to science. Mary says that George Gey sent HeLa all over the world, And pretty soon she was in hundred of labs.

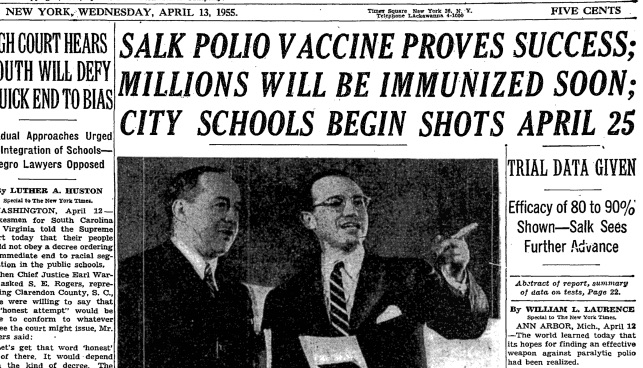

This was during the early 50's, when Polio was at its worst. There was this enormous effort to develop a polio vaccine, but, in order to develop a vaccine, you had to have enough poliovirus to be able to study in a lab. And they had no way of making enough.

Chapter 3

That was until Dr. Jonas Salk, who had recieved some HeLa cells, discovered that they copied polio exceptionally well. His initial tests of the vaccine proved effective, so the government made a factory at the Tuskegee Institute.

The cells that were produced at this factory, she says, were used to test the polio vaccine. The tests they were doing were enormous. It was the largest field trial ever done. At it’s peak, the Tuskegee HeLa production center was producing about six trillion cells a week.

But that was actually only the beginning. Because that factory led to an even bigger one that was for profit. It was the first time any human biological material was commercialized.

Once HeLa cells started being mass produced, they infected HeLa cells with every kind of virus. Hepatitis, ecoin, encephalitis virus. Yellow fever. Herpes. Measles, mumps, rabies, whatever. And this was a revolution for scientists. There was research on chemotherapy drugs, HeLa cells even went up in some of the first space missions

By the late 60s, HeLa has led to a revolution in science and now there are hundreds of cell lines, not just HeLa, but hundreds. And somewhere along the way, scientists discover that HeLa is so aggressive that they're actually contaminating and taking over other cell lines because they can float on dust particles

So on the heels of this catastrophe, someone at Hopkins decides to make a test. Let’s make a test that will allow us to genetically determine if a cell is HeLa or if it isn’t. And to make a long story short, this desire for a genetic test led scientists, and then journalists, to ask a questions which amazingly for 25 years had not been asked: Who was this woman?

And that’s when we found out her name.

Henrietta Lacks.

Chapter 4

Henrietta had five kids when she died at the age of 31. Most have no memory of her, because they were too young. And that’s especially true of her daughter, Deborah.

She spent most of her life longing to know her mother. "I was only 15 months old [when she passed] and I don’t remember anything about my mother. You know I always wanted to know what she liked to do, where she went, what she liked to eat..." said Deborah

So in 1973, when a scientist calls the Lacks family and Deborah hears that little bits of the mother that she never knew are still alive. And oh by the way, we’re having some contamination problems, so can we take a blood test from you and your family? You could imagine it was a bit of a shock.

"Took me by surprise, it really did. It was really confusing. I mean, how much is that--how much of her cells is out there?"

- Deboarah Lacks

Eventually she went online, did some searches, and found Thousands and thousands of hits. Like HeLa clones. And Deborah had heard various journalists compare what they did with her mom to Dolly the Cloned Sheep. Since the first cloned cells were her HeLa cells, that’s actually where the technology started. But that was just cloning a cell. Not cloning an entire being

But that distinction is very complicated, particularly for somebody who doesn’t know what a cell is.

So Deborah between what journalists had told her and googling Henrietta Lacks and clone, thought there were thousands of clones of her mother around. One of Deborah’s biggest fears was bumping into one of these clones

She would say, "I would have to go talk to her and she wouldn’t know I was her daughter, and I don’t know if I could handle that."

It sounds so fantastical, but it’s actually not that crazy. Because your DNA is in your cells, so if your cells are taken out of you and they still grow, well isn’t that still you?

It’s part of you, but it’s clearly not you, and it’s going on and on--it’s a funny middle space, that’s for sure.

Chapter 5

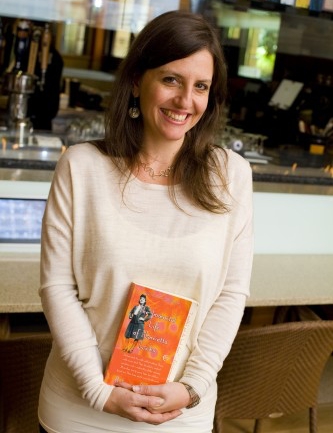

Deborah sometimes tagged along with biographer Rebecca Skloot as she went off in search of Henrietta Lacks. Every so often, Deborah would sit with her as they interviewed anyone they could find. And eventually, over many many years, a picute of her mother does emerge.

Deborah sometimes tagged along with biographer Rebecca Skloot as she went off in search of Henrietta Lacks. Every so often, Deborah would sit with her as they interviewed anyone they could find. And eventually, over many many years, a picute of her mother does emerge.

Henrietta Lacks was born in Roanoke, Virginia in 1920. She was the tenth of eleven children, but she stood out.

Everybody talked about her as just being "the catch". Brown eyes, long hair, nice tan complextion. She was really meticulous about her nails and always painted them red. And she had this strength about her.

Unfortunately, there’s not a ton of detail about how she lived. But medical records and an autopsy report give a look into how she died.

Rebecca Skloot, the author who investigated and wrote about Lacks story says she was in a pretty unbelievable amount of pain. She complained of pain in her right lower quadrant. Wailing and crying and you know, moaning for the Lord to help her.

"And she would have these fits of pain," Skloot found in the records, "Sort of spasm where these waves of pain would hit her and she would rise up out of the bed and thrash around. So they strapped her to the bed and her sister, along with one of her friends, you know, one of them would tighten the straps and the other would put a pillow in her mouth so that she wouldn’t bite her tongue"

According to the records, doctors tried everything. They even injected a hundred percent alcohol straight into her spine

For Deborah, her mother was alive in these cells somehow. So if that’s true, that left very big question: And the first of them for Deborah was, how can Henrietta rest in peace when part of her, part of her soul, is being shot up to the moon and injected with chemicals?

She worried that it hurt her mother when you infect the cells with ebola, does somehow her mother feel the pain that comes with ebola?

No scientist ever sat down with her to explain you don't feel what your cells do after they are removed from the body.

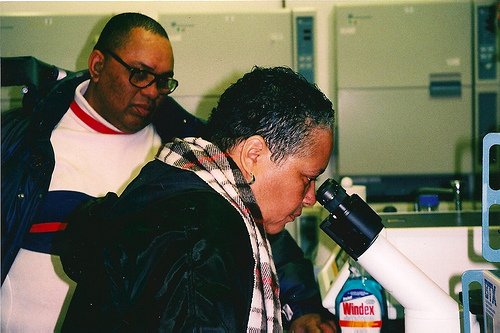

That was until Christoph Lengauer, a scientist at Hopkins, contacted Deborah Lacks and Rebecca Sloot. He invited them into the lab to see her mother's cells.

They were projected on a screen at about 200 times their actual size and tinted with green dye so they could be seen. Deborah was in awe that all of those cells had really come from her mother

"So they’re very ethereal looking. They’re very sort of--they glow, you know. I mean when you think about angels, right, you think about something glowing. Christoph turned on this screen and, I mean, Deborah just gasped."

- Rebecca Skloot

Lengauer the gave her a vial of these cells for her to hold. They came out of a freezer so they were very cold. She rubbed the vial with her hands together and blew on them, to sort of warm them up. And she just raised them up to her lips and whispered:

"You’re famous, but nobody knows it."

Chapter 6

Unfortuantely Deborah passed away in 2009, just before the book was published. She died of a heart attack in her sleep.

Since the publication of that book, the whole story just took off. Scholarships and monuments were named after Henrietta. She was given an honorary doctorate. Highway placards and historical landmarks and buildings named after her. There’s a even a high school called Henrietta Lacks High (HeLa High for short).

Skloot went on an extensive book tour, and members of the Lacks family began to join her. It started off with just Sonny Lacks doing a Q & A on stage and people started cheering. Scientists would stand up saying, "I want to tell you what I did with these cells and I want to tell you why this is important for me and I’m sorry it was hard for you."" And people reaching out, "I’m alive today because of this--a drug that your mother’s cells helped develop," It never stopped. It was like a flood.

Which is, in a way, what Deborah always wanted.

She wanted to go to every event. She wanted to be on every television show. She had her dress picked out for Oprah eight years before the book came out. This was exactly what she always dreamed of.

Chapter 7

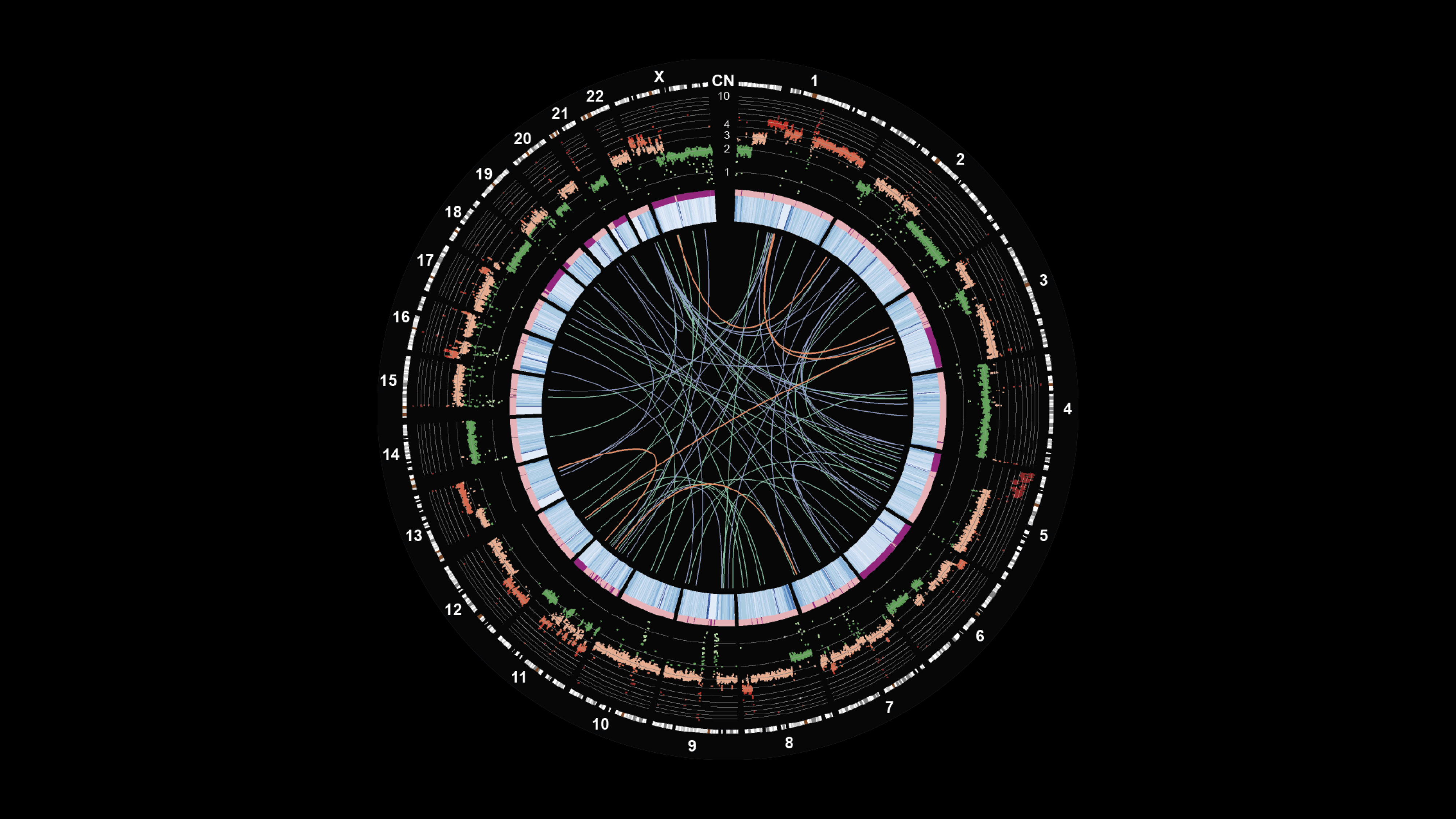

But then, in March 2013, this group of scientists from Germany sequenced the HeLa genome and published it online, where the public can download it. And, once again, they did not ask the family.

On the press release, it had a frequently asked questions section. And one of them was, can you learn anything about Henrietta or her children from this genome? And the answer was "No. You can’t learn anything about them."

They may have believed this. But this is a misconception. Within the HeLa genome, there’s also Henrietta’s genome. You can in fact learn about people, and you cannot even hide people's private information even if you try.

By sequencing the genome, the researchers essentially created a report on Henrietta’s genes. It can show a descenents chance of bipolar disorder, alcoholism, obesity, etc. A huge range of information that has some real potential privacy violation.

It caused Lacks family concern because they weren't involved with this decision making. Their first question was, can you get them to take it down?

Skloot reached out to the scientists. They replied immediately and took it offline. Then, she contacted Francis Collins, the head of the NIH, as well as Cathy Hudson, who used to to run the Genetics and Public Policy Center at Johns Hopkins.

Several weeks later, the Lacks family and Rebecca Skloot had a meeting with NIH. The directors listened to their concerns and answered their questions about basic science of genomes and what it meant to the science community.

There were several options on how to proceed, but it was decided to release the data with restrictions. The NIH would house the genome on their own servers and, in order to get access to it, you have to send in an application that about the research it would be used for.

Applications would then be approved by the The HeLa Genome Committee. Composed of a group of scientists and some members of the Lacks family, David Lacks and Veronica Lacks.

The news about their first batch of applications came out soon after. It was the first time that the third and fourth generation was part of the story.

Deborah was the one who was just so forceful and dedicated, but she is gone. This is their story now, and Granddaughter Jerry Lacks found it to be pretty exciting.

"We are stepping into the spotlight," she said.